by Mark Chapple

Snake –necked turtles are a hardy reptile that take to captivity well. While they can live in a heated tank for many years, we decided to build an outdoor enclosure for Shelley, our turtle. It would be a simple matter to have and indoor for winter and an outdoor enclosure for the summer months but the climate is mild enough, with no frosts and rarely any sub-zero temperatures, for Shelley to live outdoors permanently and they were known to live in the local wetlands.

There were a few things that had to be taken into consideration. We needed a pond big enough to house a snake-necked turtle and some aquatic plants so she could hide amongst them. The turtle also needs to be able to get out onto dry land. It also had to prevent escape by digging (we also pop the blue tongues into the enclosure during the summer months), too high to climb out of and also have enough protection to prevent predators (birds, foxes) taking any animals from within the enclosure.

Initially we tried to build a concrete pond. A large hole was dug and chicken mesh used to mould the shape within the hole and hold the cement in place. This worked well and the pond looked quite good. However we treated the cement to prevent leakage. This was unsuccessful as the treatment leached into the water and poisoned it. It seemed to keep on coming out of the cement, no matter how much we kept on changing the water so we decided to break this down and opted for a heavy duty plastic liner. There are probably non-toxic water treatments available but we had no knowledge of these at the time.

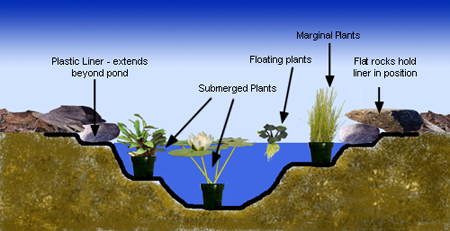

It was important when digging the pond hole to make tiers for the various plants within the pond and also to make tiers around the top edge for the plastic liner to then have flat rocks placed on it and hold it into position. The liner also extends out beyond the holding rocks into the mulched area, hiding it and making the whole scene more natural (see diagram). You need to make sure that the lining piece is large enough to go down into the pond, cover the tiers and also extend out beyond the pond boundaries.

The enclosure itself is made from sturdy timber posts. These are buried into the ground and timber walls are attached to timber on the side of the posts. Solid timber pieces go around the top so people can sit on them and look into the enclosure.

Around the base of the enclosure between the posts we hammered thick wire (fencing wire) pieces about 8'' into the ground every inch or so (we actually cheated and bent 16'' piece into a U shape and hammered these into the ground). These create an underground “cage” that prevent the animals digging their way out. An alternative is to bury iron or cement sheeting into the ground to a depth of about 8-10 inches.

Once the enclosure was completed we planted some hardy native plants and grasses, added some timber and iron sheets and mulched the entire area. To stop the predators we purchased some bird netting and some elastic “rope”. The "rope" was threaded through the netting to make a cover that can be stretched over the top of the enclosure and removed easily for access.

Shelley has been living out there for three years now and is very happy – turtles seem to smile. She always comes to the surface to say hello (probably to check for food if I was honest with myself) and we sometimes find her sunning herself on the rocks.

If you have the room around your home I can recommend an enclosure like this. Visitors love to sit around it and if it’s well made it is a decorative and functional addition to any garden.

Outdoor pond - side view detailing structure.

Below is a series of images of the turtle enclosure. Click on images for larger view in new window.

by Justin Julander, Australian Addiction Reptiles

Introduction

Children's pythons come from the North of Australia and on some offshore islands (Barker and Barker, 1994). John Grey named this python after his former mentor and supervisor, John Children. They are also called the faded python due to the reduction of pattern as they mature. Children's pythons start out as vividly patterned snakes, which in time becomes reduced as they mature. They inhabit many different habitats, and because of this adaptability are well suited to do well in captivity. In the wild, children's pythons feed on lizards and frogs when young, and may include some mammalian prey as adults.

Care

These small pythons are easy to maintain if basic needs are met. These, as well as all pythons, need a thermal gradient so that they may choose from a range of temperatures, which temperature they need to do a certain job. These jobs include digestion of food, reproductive cycling, energy conservation, and many others. No one temperature will suffice and a range of temperatures must be provided. I keep my children's pythons in cages with stacked hides below a basking light. This allows different levels of heat at the different levels of hide boxes. The snakes can therefore choose which level they want to get a certain temperature. The use of an infrared temperature gun makes this job of temp monitoring an easy task. These tools are very useful and I recommend getting a thermal temp gun to anyone that is keeping reptiles. Temperatures are everything with reptiles, so be sure you know what temps your captives are allowed to use.

I keep pairs or trios in a spacious terrarium with sand as a substrate. The sand is replaced when needed, and spot cleaned weekly. Care must be taken when housing multiple snakes together that they do not attack each other during misguided feeding responses. Water is provided in a bowl that can not be easily tipped over. In addition to the dry leveled heated hides, I also provide a moist hide filled with slightly damp green moss. This allows the pythons to choose a more humid environment when needed. If these basic needs are met, little problems will arise.

The most important aspect of keeping reptiles is observation. As all setups and methods of keeping animals vary, there is no one way. The snakes know best what they need, and their needs must come over any care sheet. For example, if you read a care page that says a snake needs a constant 80 degree heat spot and you follow that advice and the snake is always under the heat lamp out in the open, this is telling you the snake is not getting high enough temperatures. This is where you must understand what the snake is telling you and adjust your care appropriately. Many are under the misconception that if they follow exactly the methods of someone who has had success with an animal, they they will also have success. This couldn't be more wrong, and the only useful information is gleaned from the animals themselves. Watch and listen to what your snakes are telling you, and only then will you be successful.

Feeding

Hatchlings are sometimes reluctant to take pink mice as a first meal. If the needs are met, then starting hatchlings on mice will be much easier. I once had a hatchling that refused mice. One day, the heating went on the fritz and the room became lethally hot. Many of my adult breeder snakes that were close to the heat source died, but one picky hatchling that would not eat, began feeding after the high temperature surge. When I have a group of hatchlings, I will first make sure they have the proper thermal gradient (70-100 degrees Fahrenheit) and then will try live pinks straight out of the nest. Some will feed on the normal pinks, but for the others I will wash the pinks and give these "unscented" to the snakes. If they still are reluctant I will use some shed skin from some of my Australian knob-tailed geckos to trick the hatchlings into thinking it is a lizard. This usually works for all my pythons.

Adults will take full grown adult mice their whole lives. They are small enough that a few adult mice makes a good meal. There is no set regimen and I usually feed breeder snakes heavily before and after breeding season. They can be ravenous, and I have even had females that were incubating a clutch of eggs eat mice during incubation. Snakes must be well fed and heavy bodied to be ready for a reproductive event.

Justin is excited about his animals and loves to share his enthusiasm and experience. Justin has been keeping reptiles for over 20 years and breeding them for the last 6 years. Justins collection includes children's pythons, womas, knob tailed and eyelash geckos, frilled lizards, snake necked turtles, green tree pythons and spotted pythons. Justins also runs a website called "Australian Addiction Reptiles"

by Michelle T. Nash

This is an edited extact of a letter Michelle sent about one of her recent herping expeditions with family and friends.

Thought I'd send those pics because this little turtle was just so cute!

It was just a days old hatchling and you can see the umbilical stump still

on the belly. There was a purpose to catching them. A friend of mine, his

name is Mike, had heard through herp-loving friends of ours that there

was a small nature museum nearby hoping to replace their larger softshell

turtle with a very small one(s). Since Mike knew where he could find some

we decided to give it a try - to help them out AND have fun. We went out

three times. The first two times we found one each time. We were using

a proven method but not having much luck. It seems they prefer to burrow

into sandy banks just under the water and when they have recently done

so you can see the disturbance pattern in the sand so you just scoop into

the sand and pull them out. At this size they can't do you much harm. They

were about 4 x 5cm. The problem was that the area he knew of had recently

changed from sandy shallow banks to sand mixed with lots of small rocks,

making it tons harder to burrow into, for us and the turtles.

There was an area about 20m long that was good loose sand but we weren't

finding any disturbances to dig into. Finally, the third time out we

were getting a bit crazed after having no luck and decided almost jokingly

that we would just start digging all about and we'd have to find one.

Surprisingly, that's just what happened! We discovered that if we raked

our fingers through the sand about 4cm deep starting about 40 cm from

the waters edge and pulling our hands towards the shore we were scooping

up babies at a rate of 6 in about 30 minutes!

So on a later date we set out to see if the nature center wanted one or all 8 and to ask them if they knew any other nature museums that might be interested in a few of those collected since they were so small and harmless at this size they make good tank mates for other turtles on exhibit. They were quite excited and were happy to call around. If there aren't homes for the rest they will call Mike back and he will release the rest where found. They are really fascinating!

They are very common thought the state of Illinois in rivers, ponds, lakes etc. They are highly carnivorous throughout their life and once they are 3 or 4 inches can deliver a nasty cutting bite! They can get to be 10+ inches - as big as a dinner plate with a very sharp jaw under their fleshy mouth.

And these odds are not too good either....

But what to do when faced with ethical delimnas?...

We would love to hear what you think of this (or any other) issue of Keeping Reptiles.

And of course, if you have any suggestions, photos, links, care sheets or whatever for upcoming issues that you'd like to share with us, please send those, too!

These could also include:

Remember - there are lots of people who would love to hear your stories. Just e-mail me at: Reptile-Cage-Plans